Photo taken by Point Scholar Shayle Matsuda at the Hawaii Institute of Marine Biologya

I’ve “come out” many times. First, my sexuality, and then years later, my gender identity (and then sexuality again). In my late 20s I also came out, announcing a career change - I was going back to school to pursue a career in the sciences. All of these experiences were different. However, the actions and the processes shared many parallels both in how I shared myself with the world and what I asked from it.

As I followed him into his office, the first thing I noticed was the life size cardboard cutout of who I thought might be one of the Jonas brothers. It was a gift from his graduate students, an inside joke within the lab. As I took a seat on one of the cream-colored couches I daydreamed about being part of a doctoral lab community that shared jokes like this. I remember initially sitting there awkwardly for a moment, not knowing where to start. Here I was, a hopeful PhD applicant, sitting in the office of a well-established PI at a prestigious university who agreed to meet with me, with no intention of working in his field. I was here for other reasons. Three months earlier I sat on my living room couch and typed the words “transgender scientists” into Google. I was looking for role models. Within seconds, a Wikipedia page returned 14 results. Twelve in the list were transwomen. Of the two transmen listed, one was dead. I was currently sitting on a couch across from the other.

Once the steps of self-realization and self-acceptance are underway, next steps can include confiding in close friends or family, and then sharing with wider social or professional circles. This was my experience as I made the life-changing decision to go back to school as I approached 30, and again as I started my gender transition shortly after. I struggled with the fact that transitioning could be career suicide, and admit that at times I almost made the choice to leave science. Throughout my life, like everyone does, I had role models and heroes. As a child, they included my parents, the X-Men, and my 5th grade science teacher. But as I grew, so too did my need for mentorship. I sought out folks who I saw parts of myself in, and worked to make personal connections with my heroes.

There was a bluebird nest that needed to be checked for hatching. I had just driven down from the city to meet an old professor from college, and as we hiked up the dry grassy hills, I confided in her all of my fears in deciding to go to graduate school. When we met for the first time, she was standing on top of a classroom desk gesturing to a room full of captivated students. I was a high school senior and I peered through the classroom window from the hallway waiting for her class to end so we could meet to talk about the program at the university. I ended up going to that university, and because of her example and guidance, committed early on to learning how to communicate science to the public. Eighteen years later, we are still friends. That day on our hike, she listened to me exhaust the list of things that could go wrong, and assured me that grad school was there whenever I was ready (I wasn’t too old), and that she was confident that I would succeed.

I remember finding myself for the first time on a list of transgender scientists on the Internet. I had recently won an academic award for community service, academic record, and overcoming adversity, and along with a much-needed scholarship came interviews, articles and my name and story on the California State University website. My reaction when I first saw it was panic. Was I ready for this? The Internet never forgets, and while I was out in my everyday life, I wasn’t sure I was ready to be outed whenever someone like a potential employer or PhD advisor searched my name. At the time, I was weighing the risk of coming out against three criteria: if it was physically safe, if it could negatively impact my career, and how much positive impact it could have. As my appearance and voice caught up, I dropped the career question and placed the most weight on the last point. I began speaking publicly and writing about my experiences, and my Internet footprint grew. I haven’t questioned it again, until now.

There was about ten minutes left in our lab meeting when there was a lull in the conversation. I looked over to my advisor and he smiled and nodded at me. I took a deep breath, looked at my six labmates, and told them I was transitioning. After I finished, he spoke up letting me and the lab know that I had their full support. Weeks later, he pulled me aside to discuss roommate arrangements for our upcoming expedition; he went out of his way to check in about what would make me the most comfortable. And while we’ve never spoken directly about it, I was thankful that after my roommate left the expedition, I was one of the only people not reassigned someone new.

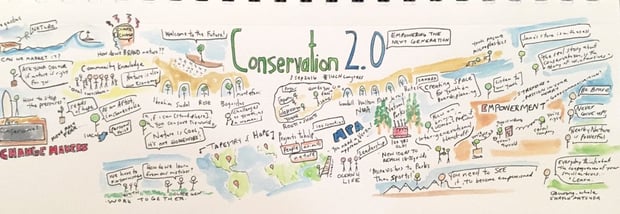

Point Scholar Shayle Matsuda shares his notes

If you’ve come to this website and are reading this blog post, you are likely to have also been paying attention since January 20th. Both the LGBTQ and Climate Change pages on the official White House website disappeared almost immediately. Amongst the atrocities of executive orders this week, in science, we have faced forced funding freezes, silencing of public communication, and threats of censorship of federal science agencies. Previously, the Trump administration requested the names of people working on climate change. Simultaneously, the administration has been making moves that threaten the civil rights of LGBTQ citizens, women, people of color, non-Christians, etc. Being identifiable on the Internet as transgender and as a scientist that studies climate change is something that is less safe now than it was just a few weeks. However, there is hope in an overwhelming and continued public resistance.

As graduate students, we straddle the line between student and teacher, novice and professional, and often mentor and mentee. From my own experiences, the moments of honesty and vulnerability demonstrated by my mentors were the most impactful. Those moments have greatly shaped my own style as a mentor. I have become who I am today in large part because of the time and thoughtfulness of many people. A small but powerful piece in the puzzle of resistance during the next four years is self-care -- it’s something we do for ourselves, others do for us, and we can do for others. My point: find your role models and mentors, learn from them, confide in them, and find strength and support from them. Reach out to your own mentees and to others, and offer support in ways you are able, because they need you, we need you, and we’ve got a long road ahead.

Photo taken by Point Scholar Shayle Matsuda

I didn’t expect to smile first thing on inauguration day. After snoozing my alarm a few times, I got up and put the coffee on and checked my email. The first thing in my inbox was a two-liner check-in from one of my academic heroes, asking how I was and if there was anything she could do to help or support me. I was fortunate enough to be able to schedule a one-time meeting with her last year, after her best-seller came out and before her move out of the country. We sat at a concrete table under the Hawaiian morning sun, each gripping hot cups of coffee, and I asked her for advice on what to say to younger students who confide in me, when sexual harassment, homophobia, racism, and sexism still plague the journeys of young aspiring researchers. I asked for advice about when in my career she thought it was safe for me to speak out. However, it was this brief email on this day that meant the most to me. A reminder that I’m not alone.

This post was written by Point Scholar Shayle Matsuda.

This post was written by Point Scholar Shayle Matsuda.

Shayle studies climate change and reef coral resilience as a Ph.D. candidate at the University of Hawaii Manoa and the Hawaii Institute of Marine Biology. Actively involved in science communication, he frequently speaks about his research and experience being a transgender scientist. Read more about Shayle here.